Boss Room architecture

Boss Room is a fully functional co-op multiplayer RPG made with Unity Netcode. It's an educational sample designed to showcase typical Netcode patterns often featured in similar multiplayer games. Players work together to fight Imps and a boss using a click-to-move control model.

This article describes the high-level architecture of the Boss Room codebase and dives into some reasoning behind architectural decisions.

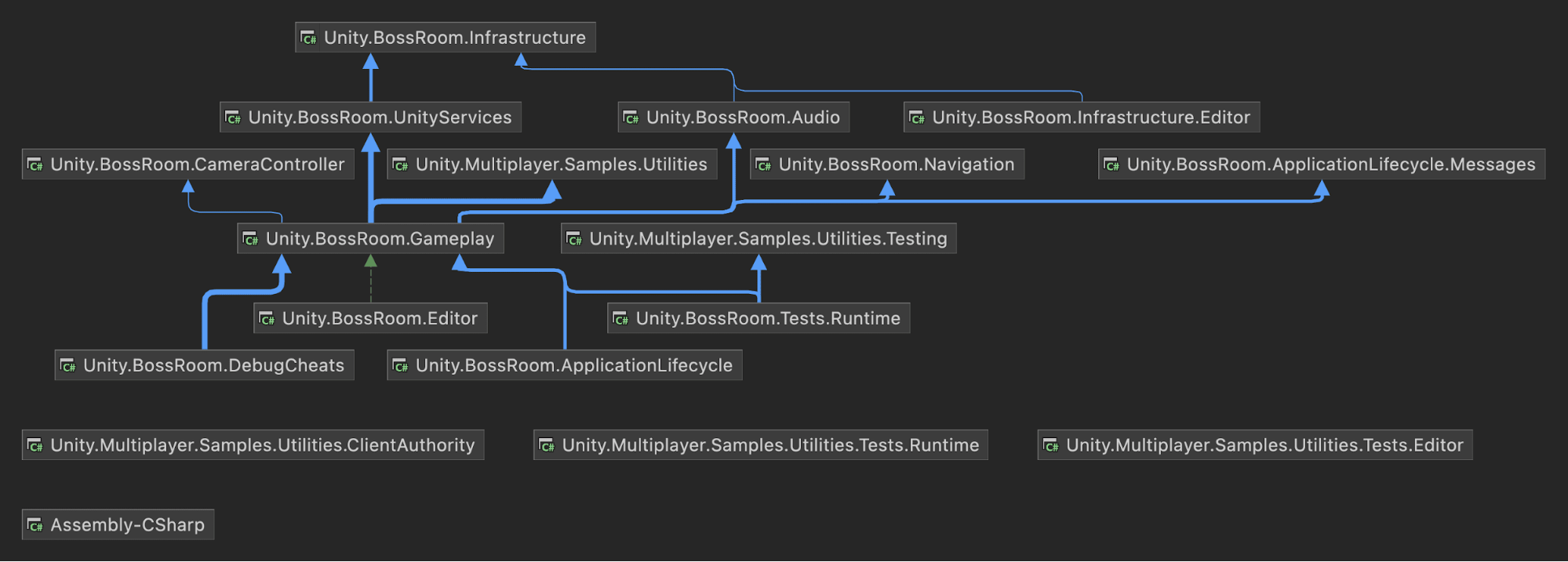

Assembly structure

Boss Room's code is organized into multiple domain-based assemblies, each with a relatively self-contained purpose.

An exception to this organization structure is the Gameplay assembly, which houses most of the networked gameplay logic and other functionality tightly coupled with the gameplay logic.

This assembly separation style enforces better separation of concerns and helps keep the codebase organized. It also uses more granular recompilation during iterations to save time.

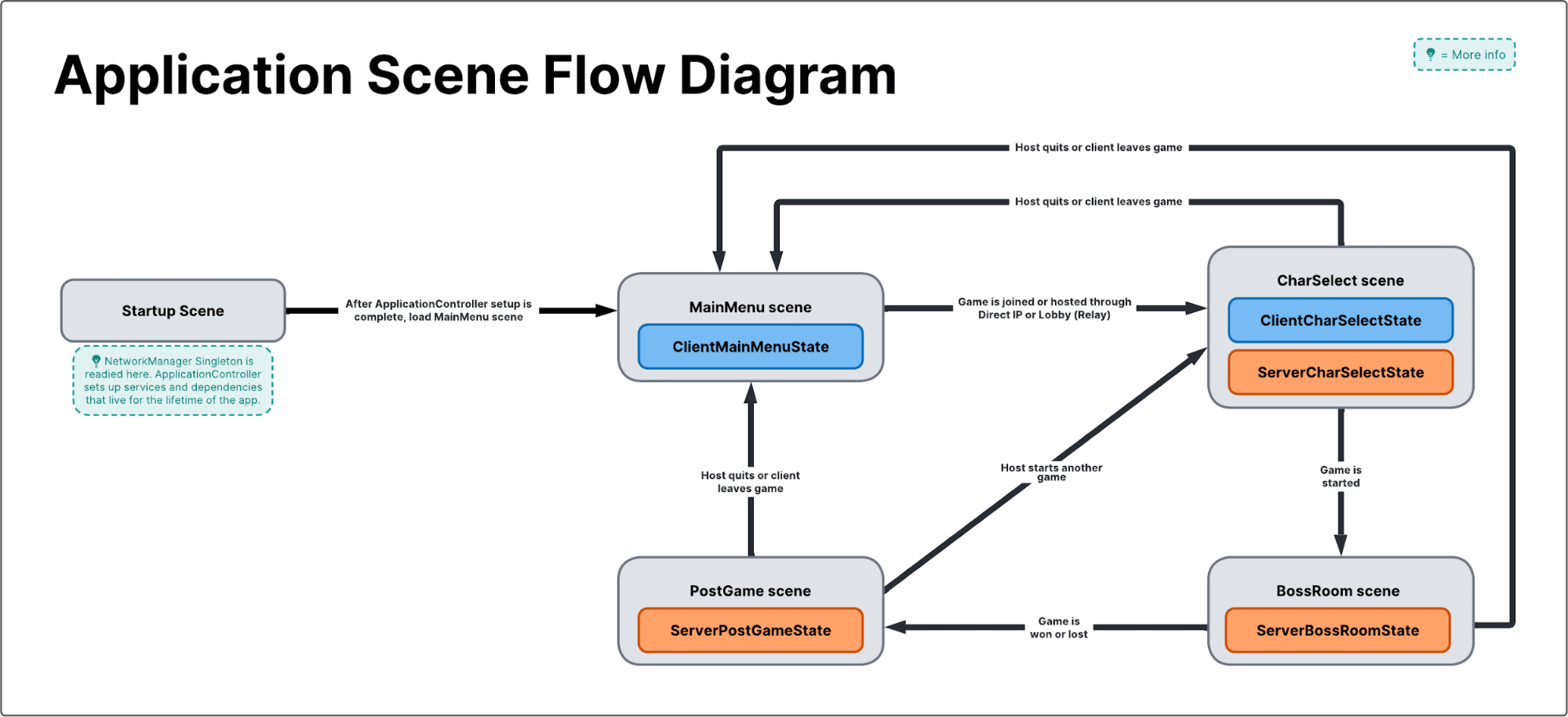

Application flow

The application flow of Boss Room starts with the Startup scene (which should always load first).

The Boss Room sample has an editor tool that enforces starting from the Startup scene even if you're working in another scene. You can disable this tool through the Unity Editor by selecting Menu > Boss Room > Don't Load Bootsrap Scene On Play. Select Load Bootsrap Scene On Play to re-enable it.

The ApplicationController component lives on a GameObject in the Startup scene and serves as the application's entry point (and composition root). It binds dependencies throughout the application's lifetime (the core dependency injection managed “singletons”). See the Dependency Injection section for more information.

Game state and scene flow

Each scene in Boss Room has an entry point component sitting on a root-level GameObject that serves as a scene-specific composition root.

After Boss Room starts and the initial bootstrap logic completes, the ApplicationController class loads the MainMenu scene.

The MainMenu scene only has the MainMenuClientState, whereas scenes that contain networked logic also have the server counterparts to the client state components. In the latter case, both the server and client components exist on the same GameObject.

The NetworkManager starts when the CharSelect scene loads, which happens when a player joins or hosts a game. The host drives game state transitions and controls the set of loaded scenes. Having the host manage the state transitions and scenes indirectly forces all clients to load the same scenes as the server they're connected to (via Netcode's networked scene management).

Application Flow Diagram

Boss Room's main room has four scenes. The primary scene (Boss Room's root scene) has the state components, game logic, level navmesh, and trigger areas that let the server know to load a given sub-scene. Boss Room loads each sub-scene additively using those triggers.

Sub-scenes contain spawn points for the enemies and visual assets for their respective level segments. The server unloads sub-scenes that don't have active players and loads the required sub-scenes based on the players' position. If at least one player overlaps with the sub-scene's trigger area, the server loads the sub-scene.

Transports

Boss Room supports two network transport mechanisms:

- IP

- Unity Relay

Clients connect directly to a host via an IP address when using IP. However, the IP network transport only works if the client and host are in the same local area network (or if the host uses port forwarding).

With the Unity Relay network transport, clients don't need to worry about sharing a local area network or port forwarding. However, you must first set up the Relay service.

See the Multiplayer over the internet section of the Boss Room README for more information about using the two network transport mechanisms.

Boss Room uses the Unity Transport package. Boss Room's assigns its instance of Unity Transport to the transport field of the NetworkManager.

The Unity Transport Package is a network transport layer with network simulation tools that help spot networking issues early during development. Boss Room has both buttons to start a game in the two modes and will setup Unity Transport automatically to use either one of them at runtime.

Unity Transport supports Unity Relay (provided by Unity Gaming Services). See the documentation on Unity Transport package and Unity Relay for more information.

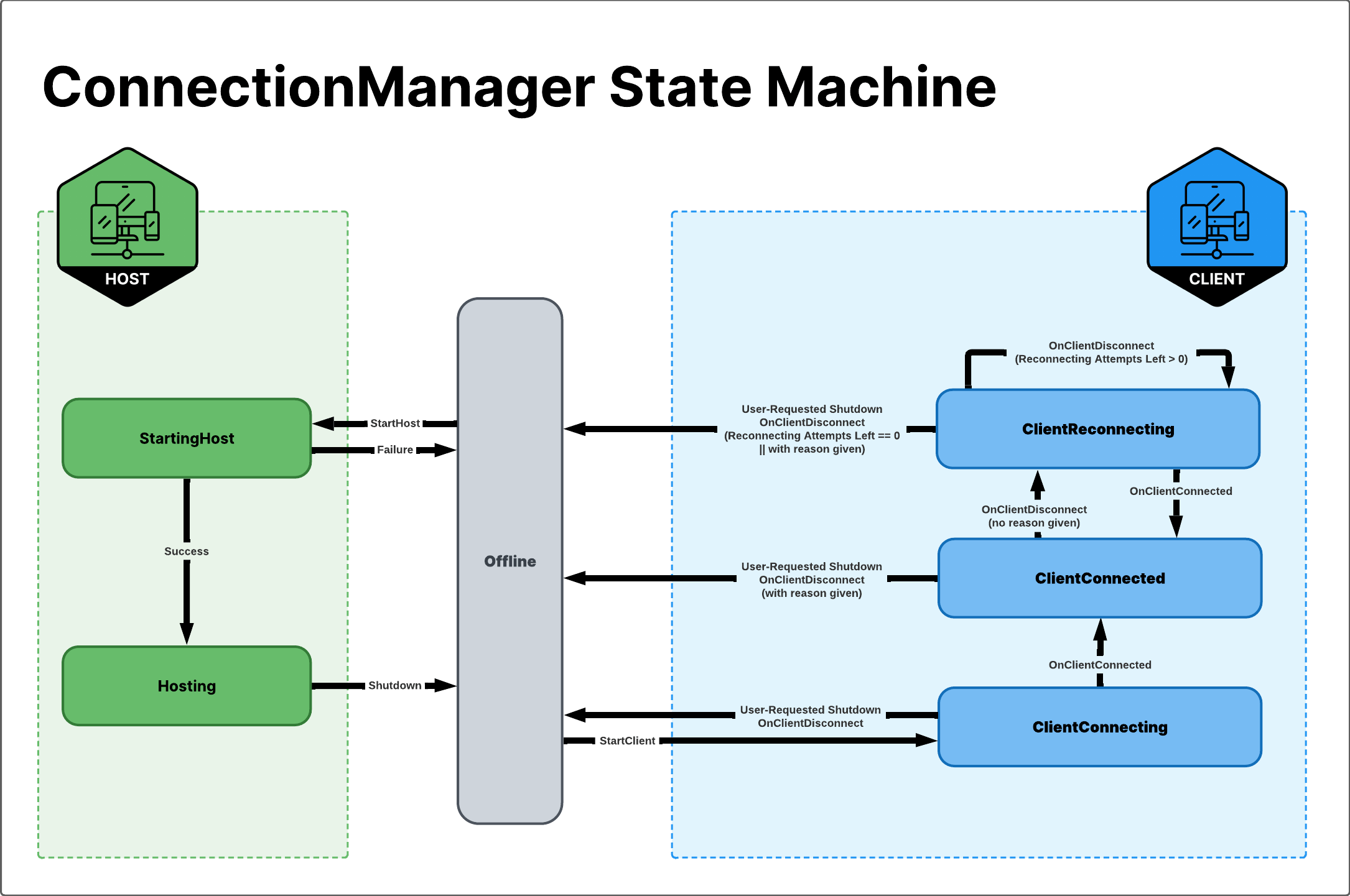

Connection flow state machine

The ConnectionManager, a simple state machine, owns Boss Room's network connection flow. It receives inputs from Netcode for GameObjects (or the user) and handles the inputs according to its current state. Each state inherits from the ConnectionState abstract class. If you add a new transport, you must extend the StartingHostState and ClientConnectingState states. Both of these classes assume you're using the Unity Transport transport.

Session management and reconnection

To allow users to reconnect to the game and restore their game state, Boss Room stores a map of the GUIDs for their respective data. This way, it ensures that when a player disconnects, Boss Room accurately reassigns data to that player when they reconnect.

For more information, see Session Management.

Unity Gaming Services integration

Boss Room is a multiplayer experience designed to be playable over the internet. To effectively support this, it integrates several Unity Gaming Services (UGS):

- Authentication

- Lobby

- Relay

These three UGS services allow players to host and join games without needing port forwarding or out-of-game coordination.

To keep a single source of truth for service access (and avoid scattering of service access logic), Boss Room wraps UGS SDK access into Facades and uses UI mediators to contain the service logic triggered by user interfaces (UIs).

AuthenticationServiceFacade.csLobbyServiceFacade.cs- Lobby and Relay - client join -

JoinLobbyRequest()in Assets/Scripts/Gameplay/UI/Lobby/LobbyUIMediator.cs - Relay Join -

StartClientLobby()in Assets/Scripts/ConnectionManagement/ConnectionState/OfflineState.cs - Relay Create -

StartHostLobby()in Assets/Scripts/ConnectionManagement/ConnectionState/OfflineState.cs - Lobby and Relay - host creation -

CreateLobbyRequest()in Assets/Scripts/Gameplay/UI/Lobby/LobbyUIMediator.cs

Core gameplay structure

An Avatar is at the same level as an Imp and lives in a scene. A Persistent Player lives across scenes.

A Persistent Player Prefab goes into the Player Prefab slot in the NetworkManager of Boss Room. As a result, Boss Room spawns a single Persistent Player Prefab per client, and each client owns their respective Persistent Player instances.

There is no need to mark Persistent Player instances as DontDestroyOnLoad. Netcode for GameObjects automatically keeps these prefabs alive between scene loads while the connections are live.

The Persistent Player Prefab stores synchronized data about a player, such as their name and selected PlayerAvatar GUID.

Each connected client owns their respective instance of the PlayerAvatar prefab. Netcode for GameObjects destroys the PlayerAvatar instance when a scene load occurs (either to the PostGame or MainMenu scenes) or if the client disconnects.

In the CharSelect scene, clients select from eight possible avatar classes. Boss Room stores each player's selection inside the PersistentPlayer's NetworkAvatarGuidState.

Inside the Boss Room scene, ServerBossRoomState spawns a PlayerAvatar per PersistentPlayer present.

The following example of a selected “Archer Boy” class shows the PlayerAvatar GameObject hierarchy:

PlayerAvataris aNetworkObjectthat Boss Room destroys when the scene unloads.PlayerGraphicsis a childGameObjectcontaining aNetworkAnimatorcomponent responsible for replicating animations invoked on the server.PlayerGraphics_Archer_Boyis a purely graphical representation of the selected avatar class.

ClientAvatarGuidHandler, a NetworkBehaviour component residing on the PlayerAvatar Prefab instance, fetches the validated avatar GUID from NetworkAvatarGuidState and spawns a local, non-networked graphics GameObject corresponding to the avatar GUID.

Characters

ServerCharacter exists on a PlayerAvatar (or another NPC character) and has server RPCs and NetworkVariables that store the state of a given character. It's responsible for executing the server-side logic for the characters. This server-side logic includes the following:

- Movement and pathfinding via

ServerCharacterMovementuseNavMeshAgent,which exists on the server to translate the character's transform (synchronized using theNetworkTransformcomponent); - Player action queueing and execution via

ServerActionPlayer; - AI logic via

AIBrain(applies to NPCs); - Character animations via

ServerAnimationHandler, which usesNetworkAnimatorto synchronize; ClientCharacteris primarily a host for theClientActionPlayerclass and has the client RPCs for the character gameplay logic.

Game config setup

We defined Boss Room's game configuration using ScriptableObjects.

The GameDataSource.cs singleton class stores all actions and character classes in the game.

CharacterClass is the data representation of a Character and has elements such as starting stats and a list of Actions the character can perform. It covers both player characters and non-player characters (NPCs) alike.

The Action subclasses are data-driven and represent discrete verbs, such as swinging a weapon or reviving a player.

Action System

Boss Room's action system was created specifically for Boss Room's educational purpose. You'll need to implement a more user friendly custom action system to allow for better game design emergence from your game designers.

Boss Room's Action System is a generalized mechanism for Characters to "do stuff" in a networked way. ScriptableObject-derived Actions implement the client and server logic of any given thing the characters can do in the game.

There are a variety of actions that serve different purposes. Some actions are generic and reused by multiple character classes, while others are specific to a single class.

Each character can have multiple actions that exist simultaneously but only one active Action (also called the "blocking" action). If a character triggers a later action, Boss Room queues it behind the current action. Non-blocking actions can run in the background without interfering with the current action.

Boss Room synchronizes actions by calling a ServerCharacter.RecvDoActionServerRPC and passing the ActionRequestData, a struct that implements the INetworkSerializable interface.

ActionRequestData has an ActionID field, a simple struct that wraps an integer containing the index of a given ScriptableObject Action in the registry of abilities available to characters. The registry of available character abilities is stored in GameDataSource.

Boss Room uses the ActionID struct to reconstruct the requested action and play it on the server by creating a pooled clone of the ScriptableObject Action that corresponds to the action. Clients then play out the visual part of the ability (including particle effects and projectiles).

It's also possible to play an anticipatory animation on the client requesting an ability. For instance, you might want to play a small jump animation when the character receives movement input but hasn't yet moved (because it hasn't synchronized the data from the server).

ServerActionPlayer and ClientActionPlayer are companion classes to actions Boss Room uses to play out the actions on both the client and server.

Movement action flow

The following list describes the movement flow of a player character.

- The client uses a mouse to click on the target destination.

- The client sends an RPC (containing the target destination) to the server.

- Anticipatory animation plays immediately on the client.

- There's network latency before the server receives the RPC.

- The server receives the RPC (containing the target destination).

- The server performs pathfinding calculations.

- The server completes the pathfinding, and the server representation of the entity starts updating its

NetworkTransformat the same cadence asFixedUpdate. - There's network latency before clients receive replication data.

- The client representation of the entity updates its NetworkVariables.

The Visuals GameObject never outpaces the simulation GameObject and is always slightly behind the networked position and rotation.

Navigation system

Each scene with navigation (or dynamic navigation objects) should have a NavigationSystem component on a scene GameObject. The GameObject containing the NavigationSystem component must have the NavigationSystem tag.

Building a navigation mesh

Boss Room uses NavMeshComponents, meaning building directly from the Navigation window fails to deliver the desired results.

Instead, find a NavMeshComponent in the given scene (for example, a NavMeshSurface) and use the Bake button on that script.

You should also ensure each scene has exactly one navmesh file. You can find navmesh files stored in a folder with the same name as the corresponding scene (prefixed by “NavMesh-”).

Architectural patterns and decisions

Dependency injection

Boss Room implements the Dependency Injection (DI) pattern using the VContainer library. DI allows Boss Room to clearly define its dependencies in code instead of using static access, pervasive singletons, or scriptable object references (Scriptable Object Architecture). Code is easy to version-control and comparatively easy to understand for a programmer, unlike Unity YAML-based objects, such as scenes, scriptable object instances, and prefabs.

DI also allows Boss Room to circumvent the problem of cross-scene references to common dependencies, even though it still has to manage the lifecycle of MonoBehaviour-based dependencies by marking them with DontDestroyOnLoad and destroying them manually when appropriate.

ApplicationController inherits from the VContainer's LifetimeScope, a class that serves as a dependency injection scope and bootstrapper that facilitates binding dependencies. Scene-specific State classes inherit from LifetimeScope, too.

In the Unity Editor Inspector, you can choose a parent scope for any LifetimeScope. When doing so, it's helpful to set a cross-scene reference to some parent scopes, most commonly the ApplicationController. Setting a cross-scene reference allows you to bind scene-specific dependencies while maintaining easy access to the global dependencies of the ApplicationController in the State-specific version of a LifetimeScope object.

Client/Server code separation

A challenge the Boss Room development team encountered when developing Boss Room was that code would often run in a single context, either client or server. Reading mixed client and server code adds a layer of complexity, making mistakes more likely.

To solve this challenge, they explored different client-server code separation approaches. The team eventually decided to revert the initial client/server/shared assemblies to a more classic domain-driven assembly architecture while keeping more complex classes separated by client/server.

The initial thought was that separating assemblies by client and server would allow for easier porting to a dedicated game server (DGS) model afterward; the team would only need to strip a single assembly to ensure code only runs when necessary.

However, this approach had two primary issues:

- It introduced callback hell, which made code (that should be trivial) too complex. You can look at the different action implementations in Boss Room 1.3.1 to see this.

- Many components were better suited as single simple classes instead of three-class horrors.

After investigation, the Boss Room development team determined that client/server separation was unnecessary for the following reasons:

- There's no need for asmdef (assembly definition) stripping because you can ifdef out single classes instead.

- It's not completely necessary to ifdef classes because it's only compile-time insurance that certain parts of client-side code never run. You can still disable the component on Awake at runtime if it's not mean to run on the server or client.

- The added complexity outweighed the pros that'd help with stripping whole assemblies.

- Most

Client/Serverclass pairs are tightly coupled and call one another; they have split implementations of the same logical object. Separating them into different assemblies forces you to create “bridge classes” to avoid circular dependencies between your client and server assemblies. By putting your client and server classes in the same assemblies, you allow those circular dependencies in those tightly coupled classes and remove unnecessary bridging and abstractions. - Whole assembly stripping is incompatible with Netcode for GameObjects because Netcode for GameObjects doesn't support NetworkBehaviour stripping. Components related to a NetworkObject must match on the client and server sides. If these components aren't identical, it creates undefined runtime errors (the errors will change from one use to another; they range from no issue, to silent errors, to buffer exceptions) with Netcode for GameObjects'

NetworkBehaviourindexing.

After those experiments, the Boss Room development team established new rules for the codebase:

- Use domain-based assemblies

- Use single classes for small components (for example, the Boss Room door with a simple on/off state).

- If a class never grows too big, use a single NetworkBehaviour (because it's easy to maintain).

- Use client and server classes (with each pointing to the other) for client/server separation.

- Place client/server pairs in the same assembly.

- If you start the game as a client, the server components disable themselves, leaving you with only client components executing. Ensure you don't destroy the server components. Netcode for GameObjects still requires the server component for network message sending.

- The clients have a

m_Server, and servers have am_Clientproperty. - The

Serverclass owns server-drivenNetworkVariables. Similarly, theClientclass owns owner-drivenNetworkVariables. This ownership separation helps make larger classes more readable and maintainable. - Use partial classes when separating by context isn't possible.

- Continue using the

Client/Serverprefix to make contexts more obvious. Note: You can't use prefixes forScriptableObjectsthat have file name requirements. - Use

Client/Server/Sharedseparation when you have a one-to-many relationship where your server class needs to send information to many client classes. You can also achieve this with theNetworkedMessageChannel.

You still need to take care of code executing in Start and Awake. If the code in Start and Awake runs simultaneously with the NetworkManager's initialization, it might not know whether the player is a host or client.

Publisher-Subscriber Messaging

Boss Room implements a dependency injection-friendly Publisher-Subscriber pattern that allows Boss Room to send and receive strongly-typed messages in a loosely coupled manner, where communicating systems only know about the IPublisher/ISubscriber of a given message type.

Because publishers and subscribers are classes, Boss Room can have more interesting behavior for message transfer, such as buffered and networked messaging. See the NetworkedMessageChannel section.

These mechanisms allow Boss Room to avoid circular references and limit the dependency surface between assemblies. Cross-communicating systems rely on common messages but don't necessarily need to know about each other. Because messages don't need to know about each other, Boss Room can more easily separate them into smaller assemblies.

These mechanisms allow for strong separation of concerns and coupling reduction using PubSub and dependency injection (DI). Boss Room uses DI to pass the handles to the IPublisher or ISubscriber of any given event type. As a result, message publishers and consumers are unaware of each other.

MessageChannel classes implement the IPublisher and ISubscriber interfaces and have the actual messaging logic.

The Boss Room development team considered using a third party library for messaging (like MessagePipe). However, since Boss Room needed custom networked channels and the use cases were quite simple, the team decided to go with an in-house light implementation. If Boss Room was a full game with more gameplay, it'd benefit more from a library that with more features.

NetworkedMessageChannel

With in-process messaging, Boss Room implements the NetworkedMessageChannel, which uses the same API, but allows for sending data between peers. Boss Room implements the Netcode synchronization for these using custom Netcode for GameObjects messaging, which serves as a useful synchronization primitive in the codebase arsenal.